The Capability Trap and Relationships

When Systems Prevent People from Using What They Know or Learning What They Need

Preamble

Companies spend millions, if not billions, trying to improve how they work. The shiny new processes, better tools, ambitious programs, and most recently the promise of AI efficiency and productivity gains. Most fail. Not solely because the methods don’t work. The failure happens in how people interact with the systems people created, constrained by beliefs people hold about what’s possible.

This isn’t about lazy workers or incompetent managers. It’s about people trapped in people built patterns reinforced by decisions people made that remain invisible until it’s understood how the pieces connect and where the influences are.

How Performance Actually Works

Two things determine how much gets done: the time people spend working and capability. Boost either one and output rises. Focus on boosting capability and impact rises.

Working harder: using overtime, working at a faster pace, and relentless pressure are levers that often produce immediate output results. These increased outputs do not last and lead to other undesirable conditions as the pendulum swings from one extreme to the next.

Improving capability: making the people doing the work and the process itself better takes time to show results. Could be weeks, months, or years depending on various conditions and complexity. These gains however are persistent. Every subsequent hour of work has a chance to produce increased work quality, and a chance for increased output, because the process improved and people are getting better at what they do.

The Grace Period

When people face a performance gap, pressure is applied to work harder. Output rises immediately and the problem appears solved.

For a period of time performance remains up. Our capability hasn’t dropped yet. This grace period, sometimes weeks or even months where people get the benefit of working harder without paying the cost of declining capability, acts as trap door.

Time is undefeated however. Unable to maintain the pace and hit targets simultaneously, shortcuts happen. Learning, practice, and slack for spaced repetition is lost. Maintenance of systems, culture, and upskilling are ignored. Documentation, although nobody really ever reads it [4], is no longer updated. In effect, all efforts at improvement are abandoned.

The Vicious Cycle People Create

As time continues in the work harder loop, eventually capability start falling. Software breaks more frequently as the quality slips. Previously solved problems resurface. Performance drops despite people working harder than ever before.

The gap is now growing and in response to not understanding the system, pressure increases. Either by people in the system pushing down, upcoming deadlines whether they are based on something real or manufactured, or declining customer satisfaction. Reacting to these symptoms people work even harder, taking more shortcuts. Capability declines faster. Performance drops further. More pressure. Harder work. More shortcuts.

This self-reinforcing cycle is the system at work. It is people doing people things. Consistently increasing the pressure to do work producing continuously declining capability results in constant firefighting to maintain barely adequate performance.

Welcome to the capability trap. The belief in the need to work harder when the actual problem is eroding capability. The system teaches people the wrong lesson, then provides evidence the lesson was correct.

What People Tell Themselves

Pressure is increased by various actors in the system from managers and stakeholders to customers and users. The output of this pressure is a rise in throughput. What these actors can’t observe are the shortcuts being taken. Invisible is the skipped training, deferred maintenance, and abandoned improvement work. This results in an overestimate of the impact of pressure.

The evidence confirms what they suspected: “We increased the pressure, output went up, people weren’t working hard enough before.”

Months or years after the pressure caused capability to erode and when performance eventually falls, these actors don’t connect it to decisions people made long ago. The conclusion is people slacked off again. More pressure must be required.

People in the system teach themselves exactly the wrong lesson. Then people create compelling evidence the lesson was correct. Then people act on that lesson, making everything worse.

The Double Bind

Organizations stuck in this pattern launch improvement programs while maintaining aggressive targets. New processes are defined and handed down. People are now faced with impossible choices while attempting to hit the production numbers AND implement the new process.

With no time to improve capabilities and the new process, people cut corners on the new process in favor of hitting their numbers. (Nobody ever got fired for hitting a deadline and very few for delivering something that didn’t work so long as it was delivered on-time and within budget. I’ve got some decent stories I could share on this if anyone asks.) People work around the system while appearing to follow it. Perhaps management discovers the shortcuts and concludes people can’t be trusted. Since people can’t be trusted, a decision must be made, the decision is to increase monitoring. In response people hide problems more carefully.

Same situation, completely different stories people tell themselves about it:

Engineers: “We never had time to use the new tools. We had to do our normal work plus learn the system. There weren’t enough hours.”

Managers: “Engineers want to forever tweak things. It’s a Wild West culture. They view process as bureaucratic.”

The capability trap doesn’t just hurt performance. It destroys relationships between people. Dysfunction becomes imbedded in how people interact, what people believe about each other, what people think is possible.

When Capability Can’t Be Used

The insidious nature of this system is when people develop capability that the system won’t let them use.

The engineer who learned better design practices but has no time to apply them. The operator who knows how to prevent defects but can’t stop the line to fix the root cause. The team that figured out a better process but isn’t allowed to deviate from the standard procedure.

People’s capability impacts system outcomes only so much as the system doesn’t prevent that capability from being used effectively.

People can train and develop their skills. Build on their knowledge. But if the system forces them to take shortcuts, punishes them for stopping to fix problems, or demands they prioritize throughput over improvement, that capability sits unused. Not only unused, but like any unused muscle in the body, it atrophies. People stop suggesting improvements because suggestions get ignored. People stop learning because learning has no outlet. Learning is not valued. People stop caring because caring makes the impossible choices more painful.

While the capability trap certainly erodes process capability. Worse, it wastes human capability by creating systems that prevent people from using what they know.

Why Time Spent Learning Is Never Wasted

The capability trap creates a cruel irony. People can know solutions to problems they’re not allowed to solve. People can see better ways of working they’re prevented from trying.

The waste isn’t the learning. The waste is creating systems that prevent people from applying their learning while simultaneously demanding they improve.

People who spent time understanding the system can fix problems permanently instead of temporarily. People who invested in learning better methods can implement them if given space. People who developed improvement skills can improve things when the system stops punishing them for trying.

Learning also does something else. learning changes what people believe is possible. Knowing a better way exists prevents accepting the current way as inevitable. That knowledge becomes the seed of change when conditions shift or can be the driver for a shift to happen.

The alternative guarantees nothing changes. Ever. Because when opportunity finally arrives, nobody knows what to do with it.

It’s Relationships All The Way Down [2]

The capability trap isn’t a tool problem. It’s not even really a people problem in the sense of having the “wrong people” or people with “bad attitudes.” Although neither of these is optimal.

“A system is people peopling.” - Chris Pipito

The system isn’t separate from the people. The system is people relating to each other in patterns people created and now maintain. Change what people believe about each other, change how people relate to each other, and the system changes because the system is those relationships.

The capability trap is about what happens in the relationships between people when those relationships exist inside structures people created, constrained by beliefs people hold, responding to pressures people applied.

“Question everything. Put special focus on our deepest held beliefs. What we trust most hides our biggest problems.” Woody Zuill

And those relationships determine whether people’s capability gets used or wasted.

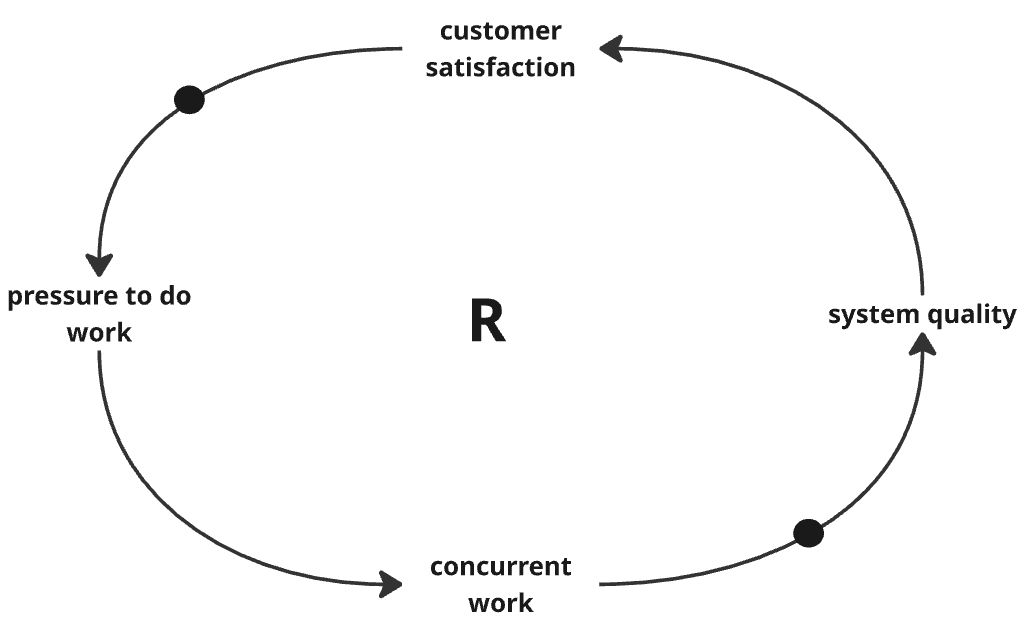

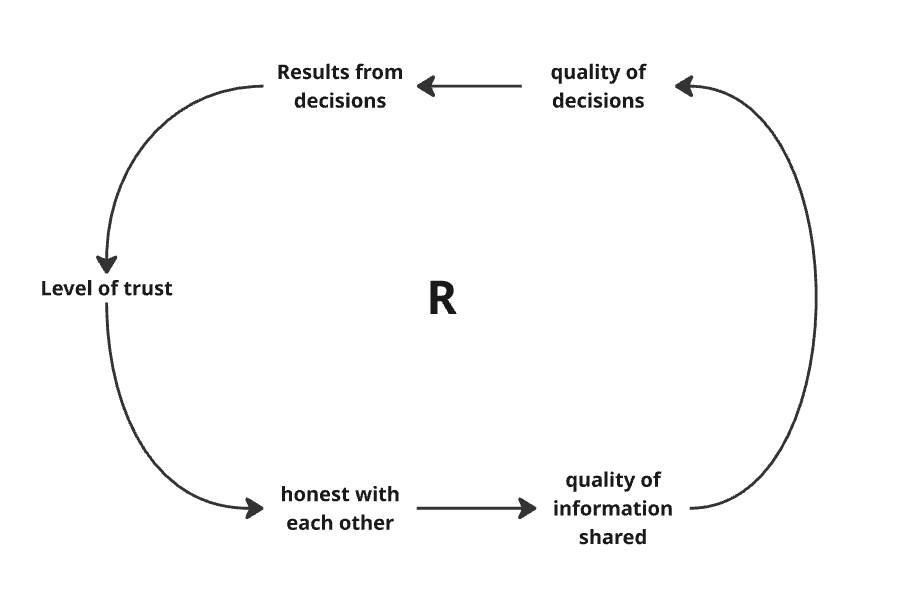

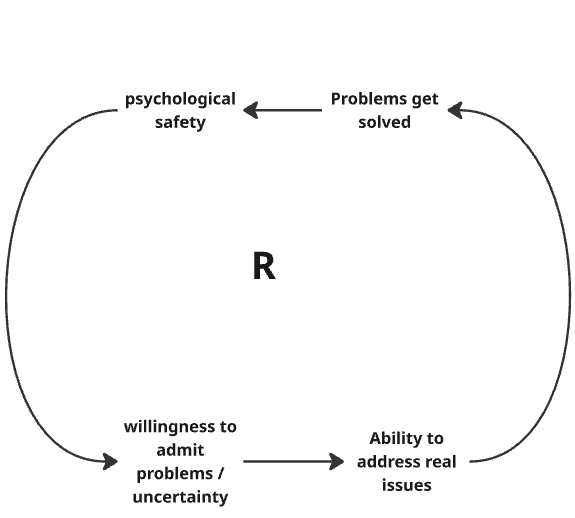

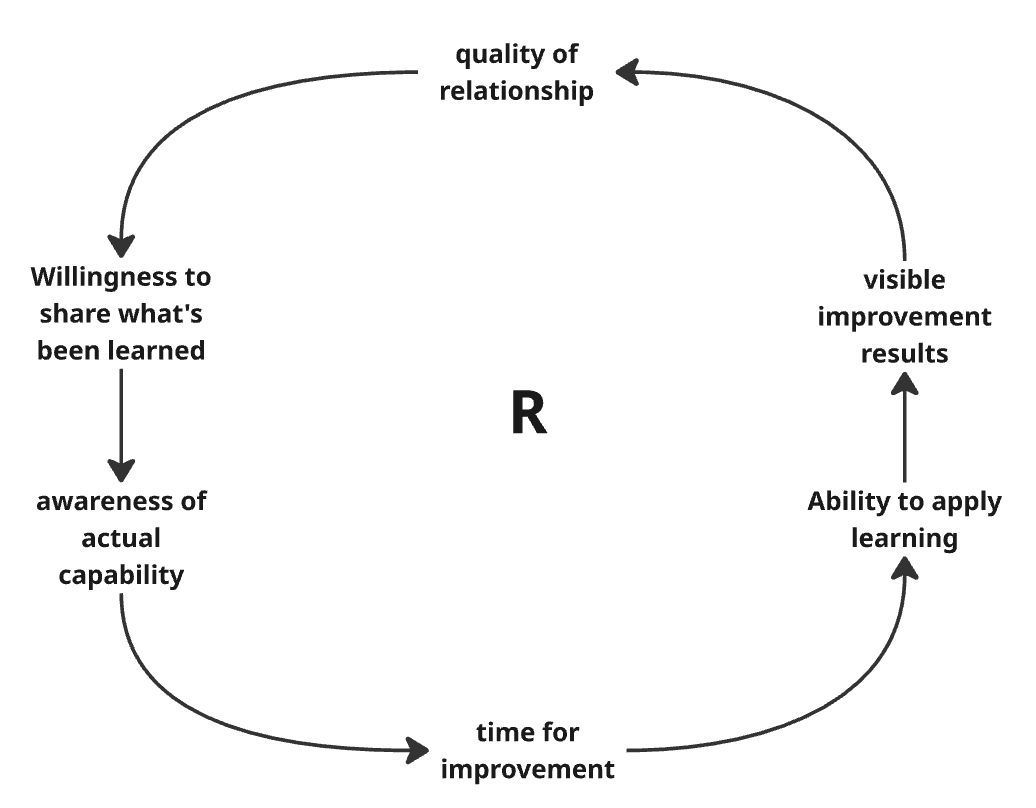

We can use causal loops, a systems thinking tool, to see the different parts of a system and the relationships and influence they have on each other.

Reading Causal Loops

Variables: part of the system. examples would be: “results from decisions”; “problems solved”; “quality of information shared”.

Links: the arrows showing directional relationship between variables

Balancing Loops: indicated by a “B” in the center of the loop

Reinforcing Loops: indicated by an “R” in the center of the loop

Influence: an arrow connecting two variables means those variables move in the same direction. Example: As “pressure to do work” goes up; “concurrent work” goes up. An arrow with a circle on it means the two connected variables move in opposite directions. Example: As “customer satisfaction” goes down; “pressure to do work” goes up.

Note about reinforcing loops: Changing the condition a variable changes the nature of the loop. Making the loop either virtuous or vicious. The descriptions of these reinforcing loops makes them virtuous.

Imagine in the quality of relationship loop changing the condition of the variable “quality of relationship” to down and walk the loop. What story are we telling now? Which story matches your current context?

The Invisible Cost

“Nobody ever gets credit for fixing problems that never happened.”[1]

Be it the maintenance that prevents a breakdown. Or the investment in knowledge creation that eliminated the error. Or the improvement work that made the crisis unnecessary.

None of it visible. None of it celebrated. All of it easily cut when pressure rises.

When capability eventually erodes and problems multiply, people assign blame without recognizing the cost of shortcuts taken months or years before. Rather than recognizing that capable people were trapped in a system that prevented them from using that capability.

What To Consider

If you are in an organization constantly in firefighting mode while improvement programs fail, you’re probably in the capability trap. The evidence you’re using to conclude people need to work harder is the same evidence created by people working harder.

The solution isn’t better tools or different people. It’s people changing what they believe about improvement, about one another, and about what’s even possible. And it’s people changing the system so the capabilities of the brilliant people doing the work can actually be used.

That change most times requires experiencing the worse-before-better dynamic of real improvement. Ironically as I write this, fully anticipating not very many if any people will read it and even if they do the reality that communication is a funny thing [5], making change and the worse-before-better can not be read about alone. Experiencing it is necessary. Seeing for yourself that investing time in improvement initially drops performance before raising it. Understanding that the grace period of working harder always ends with declining capability has to be a reality for you in your context.

Most importantly, it requires recognizing that systems are people peopling. The capability trap exists because people created it through relationships, beliefs, and decisions. And those same relationships either unlock or waste people’s capability.

Which means people can escape the trap the same way through changing relationships and challenging deeply held beliefs. And by changing what the system allows and rewards.

First people have to see they’re in it. And see that having capable people isn’t enough if the system prevents them from using that capability effectively.

What You Can Do

Some systems thinking tools, causal loops, variability, u-curves, failure demand, and value demand can be valuable understanding the system you are in.

Reading, and sharing, the paper referenced that created this article “Nobody Ever Gets Credit for Solving Problems that Never Happened: Creating and Sustaining Process Improvement”.[1]

Invest in your people. Make space in their work for upskilling and practicing their craft. Avoid sending people to training sessions a few times a year and look for ways to make capability improvement part of what they do. I hear great things about immersive learning environments.

Study the system. Model the system and share what you find with anyone interested. If its visible, its valuable. Nobody ever solved problems that remained hidden or ignored.

Make it safe to learn. Prioritize learning goals with people and across teams. And by prioritize, perhaps start with having some learning goals.

Slow down: understand problems. Do not rush to solve the symptoms of the system. Take time to figure out if what you are seeing is a signal of the actual problem that needs solving.

Tell the story of your team and your org. Talk about how work happens in your team and in your org. Talk about how learning happens. Tell this story to others in the organization. Chances are not only are they interested, they will have stories of their own that you can learn from as well.

References

[1] Sterman, J. and Repenning, N. 2001, “Nobody Ever Gets Credit for Solving Problems that Never Happened: Creating and Sustaining Process Improvement” https://web.mit.edu/nelsonr/www/Repenning=Sterman_CMR_su01_.pdf

[2] GeePaw Hill “Its Relationships All The Way Down”

[3] Reinertsen, Donald G., “The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation” Lean Product Development. Celeritas Publishing, 2009.

[4] Pipito, C. and Meadows, K. 2024, “The Hidden Saboteurs of Software Engineering, Part One: Documentation Practices: How We Unwittingly Sabotage Our Best Efforts”

[5] Wiio, Osmo A., 1978 “Wiios Laws” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiio%27s_laws